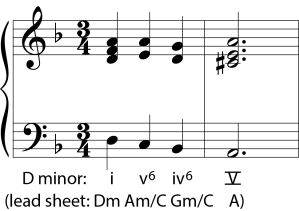

The term “descending tetrachord,” also “lament bass,” generally refers to a descent in a bass line by step from tonic to dominant, especially in a minor key. In its simplest form, the difference between the stable first and last pitches (do, sol) and the middle pitches (te, le) is reflected by the strength of the opening and closing harmonies, in root position, and the middle harmonies, in first inversion.

This progression is so “driven”–the bass moves inexorably down by step, and often so do the upper voices–that one hardly pays attention to the harmonic function of the middle harmonies. The forward-motion is accomplished mostly through that voice leading, rather than through strong harmonic progression (except on the large scale, tonic->dominant).

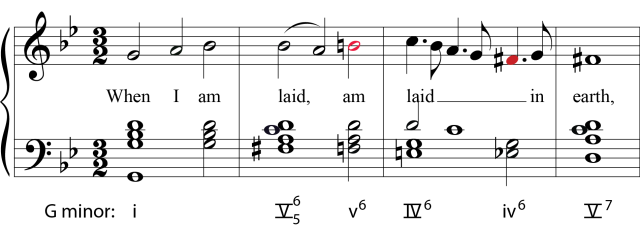

The cool thing about that is that, as long as one maintains the sense of voices inexorably moving from the tonic to the dominant, one can put some pretty wacky chords in the middle of the progression without destroying its integrity. Perhaps the most famous example is from Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas, in the aria often called “Dido’s lament.” The entire aria is laid over repetitions of a short bass line, which begins with a descending tetrachord followed by a brief cadence. It starts pretty plain, as in the example here (slightly simplified), with just a few additions to the basic formula: the bass adds some chromatic passing tones, there’s a suspension in the voice at the beginning of m. 2, and there are some other intensity notes in the voice (in red) that can be explained pretty easily.

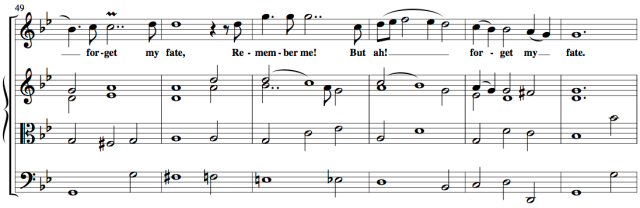

By the end of the aria, the progression is much more colorful, as shown in the excerpt below from an edition on imslp (go here, scroll down to the sheet music section, and find Act III: Dido’s Lament). I haven’t labeled chords because there’s not much point. It’s all about voice leading, and the driving descending motion is emphasized by all the suspensions (look for notes on the downbeat slurred into the next note).

Compare these two excerpts at 0:14 and 2:18 in the Spotify recording below, or 1:12 and 3:35 of the Youtube video, which includes a score. (Listen from the second excerpt to the end, which gets even more colorful.)

Okay, finally to rock music, Muse’s MK Ultra. This is a song that has a strong sense of voice leading throughout, unlike some rock, and it’d be fascinating to trace this throughout the song, but just one section directly relates to descending tetrachords. Here’s a simplified version of the backing vocals and bass for the final chorus. (The lead singer participates too, but in more complicated ways.) To hear the progression, check out around 3:12 in either recording below.

This progression is an update of Purcell’s: through the chorus, the bass moves slowly from tonic (D) to dominant (A), and the beginning and ending harmonies are tonic and dominant as expected. In between, we get all kinds of sweet chords, including a secondary dominant tonicizing V in m. 3 and a “cadential 6-4” in mm. 11–12 and, more clearly, mm. 13–14. The very long time it takes to get to the ending dominant keeps the progression intense and interesting. So does the harmonic progression, which actually is not so difficult or strange as it might at first seem.

But so does the voice leading. Start on any note in the first chord–D, F, or A–and you can (with only very slight detours) follow it either to the same note or downwards as it moves from chord to chord, with two places where such voice-leading routes leap up by octave indicated by arrows. For example, the D at the bottom of the “right hand” at the beginning stays on D in m. 3, moves to C# in m. 4, C in m. 5 (now up an octave), Bb and A in m. 6, G in m. 8, G in m. 9 (now in the middle of the “right hand”), F# and F in m. 11, E in m. 12, D in m. 13, and finally C# in m. 15.

Essentially, they’re doing the same thing Purcell was doing: using the inexorability of the voice leading–highlighted here not just in the bass but in the other parts as well–to make this colorful, somewhat crazy progression make linear sense. (For why Muse might have wanted a “crazy” progression,” check out what the song is about.)

One last thing to mention: the first chorus of the song doesn’t have such continuous backing voices. But follow the voice leading I’ve given for the final chorus as you listen to the first chorus around 1:19 in the recordings above, and I think you’ll hear that it even underlies this less-continuous chorus.

Pingback: Panaszok a mélyben | SUNYIVERZUM